Brand Simplicity: As the world becomes more complex, simplicity reigns supreme

One of my basic brand principles states that the more complex the technology or the science, the simpler the brand message should be. When marketing their products or services, companies violate this principle at their own risk.

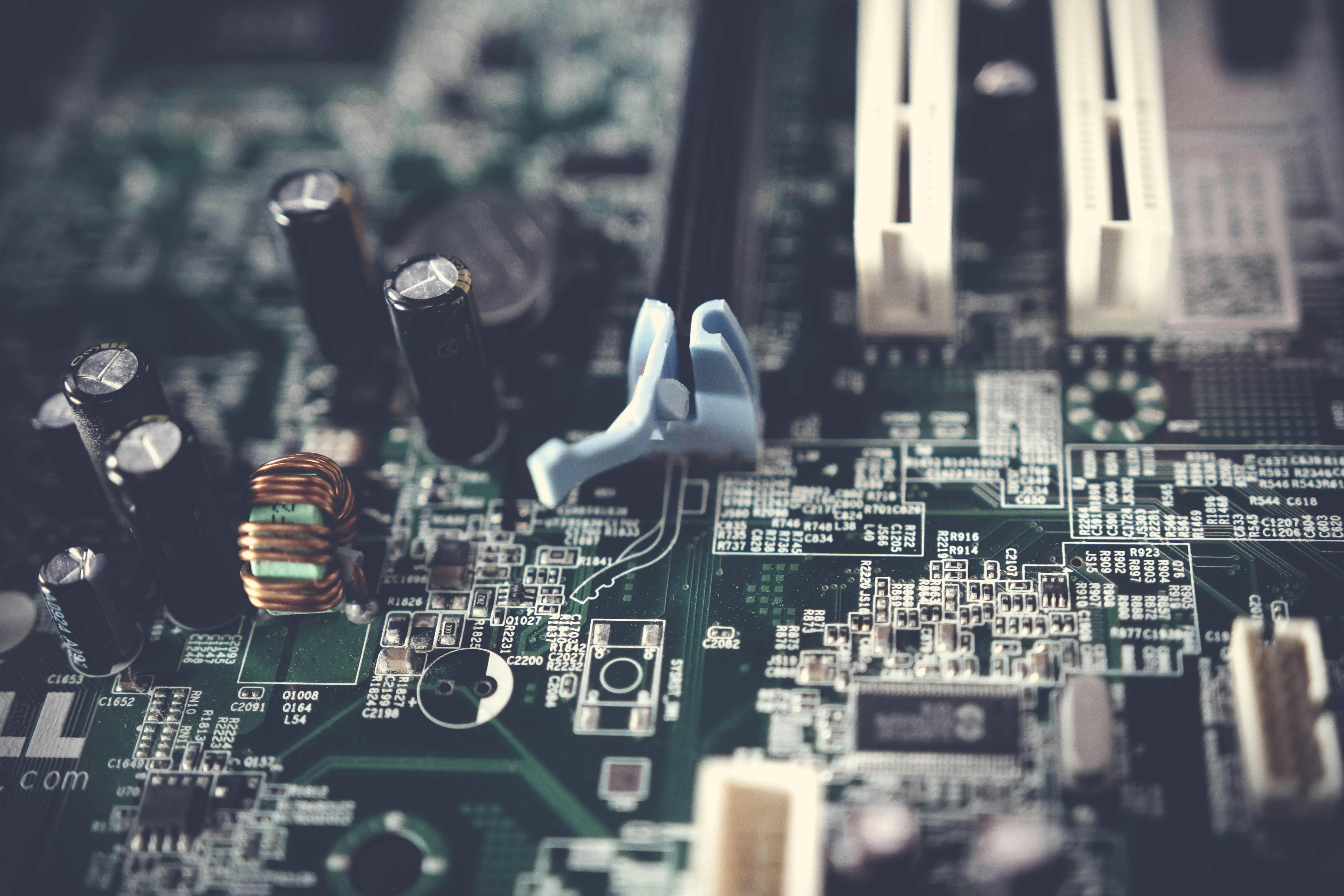

Evidence for this principle abounds in the world of consumer electronics.

In a 2002 survey, the Consumer Electronics Association found that 87% of people rated “ease of use” as the most important factor when considering a new technology. Lately, it seems that many companies have rediscovered the strategy of simplicity and are incorporating it into their products and messages. But before we examine these newcomers to the simplicity scene, let’s take a look at a couple of pioneers who have stayed true to the principle of simplicity for a long period of time.

No company in the world of consumer electronics understands simplicity better than Bose. While the technology that drives Bose’s innovations is quite complex, the consumer interface has always been simple. The result is industry-leading sound quality with interfaces that consumers can understand in seconds, without reading the user manual.

In the 1950s, Dr. Amar G. Bose noted that loudspeakers did not produce natural sound. In 1968, after extensive research into the science of sound, Bose introduced the legendary 901 Direct/Reflecting loudspeaker, which reflects 89% of sound off walls (similar to a live concert) for natural, realistic sound. In 1975, Bose developed the 301 series, which became one of the best-selling loudspeakers of all time. Since then, Bose has introduced a new product every few years, such as acoustic noise-canceling headphones, the Wave radio, and the 3 2 1 home entertainment system, that capture consumer interest.

The result of following this simplicity strategy? Millions of satisfied customers, a spot on the Forbes Weathiest 400, and an estimated net worth of $900 million for Amar Bose.

Henry Klaus offers another example of a design engineer who understood the importance of simplicity. His Tivoli Audio Kloss Model One, an AM/FM tabletop radio with amazing sound quality, has been on the market for more than half a century. You won’t find a better desktop radio for $125, and it fills a room with high-quality sound that compares to systems costing thousands of dollars more. Klaus also innovated the first acoustic suspension speaker that became the basis for the Advent speaker, which became the reference design for all subsequent speakers. When he passed away in 2002, Klaus left behind a long legacy of technical innovations that bordered on genius but always kept it simple and clean in the interface with consumers.

Opposite ends of the spectrum

At the other end of the simplicity spectrum is Sony.

Most analysts attribute Sony’s recent woes to a lack of innovation, a true Achilles’ heel for leading product companies striving to deliver the “best product, period” value proposition. I agree that a lack of innovation tops Sony’s list of challenges, and rightfully so. However, I submit that the second to fifth reasons have to do with overly complex products.

As I write this blog, a Sony DA5ES receiver sits next to me on my desk. It has enough power to simulate a California earthquake, but it also has enough complexity to confuse a Stanford engineering doctorate. This receiver has no less than 37 buttons and knobs on the front panel, most of which I have no idea what they do. Worse yet, neither do my teenagers, because after messing with all 37 knobs it really does sound bad. In today’s world, if a teenager can’t figure out a technology, he knows it’s too complex.

Current leaders in the simplicity movement include TiVo, Skype’s Voice-of-Internet service, Google’s search engine, Intuit’s Quicken, and RIM’s Blackberry. But the real shining star in the simplicity category is Apple’s iPod. The iPod has been this year’s big success story for many reasons. At the top of the list, however, is its simplicity.

Other manufacturers tried for years to gain a dominant market share in the MP3 player market, but their products were too complicated, confusing, or difficult to use. Apple cracked the nut with a simple design for both the iPod and the accompanying PC software, iTunes. As a result, Apple has sold more than 20 million iPods to date and has a 75% share of the MP3 market. More importantly, Apple has seen an eight-fold increase in its stock price as a reward for its simplicity.

The dark horse of simplicity

While Apple may currently be leading the way, I see a real dark horse fast approaching in the race for simpler consumer electronics: Royal Philips Electronics.

By the late 1990s, after decades of relentless Asian competition, Netherlands-based Royal Philips Electronics had become a slow sloth whose products, ranging from medical diagnostic imaging systems to light bulbs and televisions flat-screen TVs were rapidly losing ground. in the market

According to an article in the November 2005 issue of Fast Company, Phillips attacked the problem of declining market share by sending researchers to seven countries to survey nearly 2,000 consumers. Your goal? Identify the biggest social problem that the company needs to address. Respondent response was strong and urgent: consumers felt overwhelmed by the complexity of technology.

According to Phillips research, around 30% of home networking products were returned because people couldn’t get them to work. Additionally, nearly 48% of people put off buying a digital camera because they thought it would be too complicated. As a result of this feedback, Phillips strategists recognized a tremendous opportunity: to be the company that delivered on the promise of sophisticated technology without the hassle. Instead of simply reorganizing products, Philips would transform into a leaner, more market-driven organization. More importantly, Philips would position itself as a simple company.

Phillips launched an internal and external campaign, titled “Sense and Simplicity [http://www.simplicity.philips.com/global_flash.html]”, which required that everything Philips did in the future had to be technologically advanced but designed with the end user in mind. It also had to be easy to experience. More importantly, each product and its resulting features had to emanate from a need This ideal now drives everything Phillips does, from product conception to development, packaging and distribution.

This drive for simplicity extends throughout the company. For example, Philips recently introduced Dynamic Lighting, which brings the dynamics of daylight into the workplace, creating a stimulating “natural” lighting environment and giving people personal control of their lighting. In this way, Dynamic Lighting enhances people’s sense of well-being, motivation and performance.

While many of Phillips’ new products have yet to reach the market, the early results of the business reorganization, particularly in North America, have been spectacular. Sales growth for the first half of 2005 was 35% and the company was named “Vendor of the Year” by Sam’s Club and Best Buy. Phillips’ Ambilight flat-panel TV and GoGear digital camcorder won European iF awards for integrating advanced technologies into user-friendly design, and the company was awarded 12 innovation awards by the Consumer Electronics Association.

My bet is that Philips will re-emerge in the coming years as a leading technology company, as Apple has recently. I don’t pretend to be an investment adviser, but I’d be surprised if we don’t see a similar rise in Phillips stock price. History shows that markets reward the ability to simplify companies and their products in meaningful ways for consumers. As Phillips seems to be learning, a little simplicity can go a long way.